Sordid Temptations

by Harlie D.

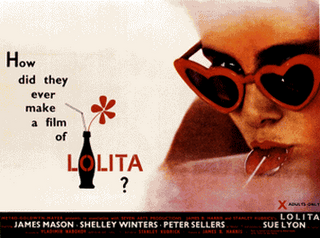

Lo-li-ta. A name that seems to embody a dark sensuality and evokes a sense of inappropriate playfulness. Exactly what author Vladimir Nabokov had in mind for his main character in the 1955 novel Lolita. The novel, later made in to a film by Stanley Kubrick in 1962, explores a middle-aged, college professor’s perverse infatuation with a young girl, who eventually comes to be his step-daughter. While the novel was originally written in 1955 it was banned in Paris from 1956-58, and was not published in its full form in the US until 1958, where Lolita’s age was raised from 12 to 14 or 15 for the American publication. The story lacks overt sexual content, yet it is full of subtle, yet inappropriate references and double entendres.

The story begins as Humbert Humbert, the professor, seeks housing while awaiting the commencement of his appointment at a university. Humbert is introduced as a European seeking “haven,” (from what, it is unclear) in the United States. What better place to seek refuge than American suburbia! In an excerpt from a summary of the film, the neighborhood is described as follows: “We're really very fortunate here in West Ramsdale. Culturally, we're a very advanced group with lots of good Anglo-Dutch and Anglo-Scotch stock. And, uh, we're very progressive - intellectually” (Dirks, Lolita (1962)). Not only does this reference seek to point out the societal prejudices of the time, but it also slightly revels the dark undertones of the story, giving a sense of uneasiness as to what ‘progressive’ actually refers to in this case.

Lucky for Humbert, an Ohio housewife, widowed for seven years, is all too eager to rent a room to such a successful bachelor. The persona of the weak, sexually starved, and desperate 1950s housewife boldly emerges early in Nabokov’s novel. Synopses of both the novel and movie versions of Lolita are void of details regarding Charlotte Haze’s life outside her emotional longing to become Humbert’s partner. She is described a “wealthy widow” and her role in the novel is to model the deep seeded angst and sexual frustration felt by so many women in the 1950s. Humbert, put off by Charlotte’s pushy demeanor, hesitates to take up residence with her, until he lays eyes on her unusually seductive, “nymphet” daughter- Lolita. A juxtaposition of characters is immediately evident- Charlotte seems to represent the housewife of the past, content in her lot, happy to be subservient even to her late husband and eager to live in the shadow of her next love interest, seeking only to love him and accept his love in return. Such lines like, “Ohh, I'm lonesome...I think it's healthy for me to be jealous. It means that I love you. You know how happy I can make you” (Dirks), epitomize the housewife image of the time. In contrast, Nabokov’s Lolita is perhaps his symbol for the woman of the future- a product of a demanding etiquette which requires a woman to suppress her libido and deny lust and even instinct. Lolita commands her sexuality, it exudes from her every action, and Humbert is immediately enraptured by her intensity. A very sordid love affair ensues between the professor and his young lust interest; in fact Humbert marries the vapid Charlotte just so he can later be with Lolita. But the whole affair eventually turns into a disaster when Humbert’s hunger for Lolita consumes him and feeling dominated by him, Lolita rebels and ultimately gets taken advantage of by another older man and ends up in a lower-class slum, pregnant and without money. Humbert goes on to murder the man who stole Lolita away from him and dies in prison while awaiting his trial. The tragic ending to the story only reinforces the pertinence of Nabokov’s social commentary.

That Lolita’s modern promiscuity ends perilously for all those involved might serve as a warning to the people of the 1950s. Not a warning that says, ‘Don’t be like Lolita!’ But rather a warning about a dangerous trend in 1950s society- perhaps such staunch resistance to human nature and sexuality causes a very unsettling dynamic within a culture, a dynamic which could result in an unhealthy eruption of emotional detachment and rage even. While considered very risqué for the time, I believe Lolita brought about a much needed social awareness and piqued an interest in people’s subdued cravings for something edgy, off-beat, and disturbing even.

WORKS CITED

Dirks, Tim. Lolita (1962). Greatest Films: 1996-2006.,/a> Online. 18 October 2006.

Lo-li-ta. A name that seems to embody a dark sensuality and evokes a sense of inappropriate playfulness. Exactly what author Vladimir Nabokov had in mind for his main character in the 1955 novel Lolita. The novel, later made in to a film by Stanley Kubrick in 1962, explores a middle-aged, college professor’s perverse infatuation with a young girl, who eventually comes to be his step-daughter. While the novel was originally written in 1955 it was banned in Paris from 1956-58, and was not published in its full form in the US until 1958, where Lolita’s age was raised from 12 to 14 or 15 for the American publication. The story lacks overt sexual content, yet it is full of subtle, yet inappropriate references and double entendres.

The story begins as Humbert Humbert, the professor, seeks housing while awaiting the commencement of his appointment at a university. Humbert is introduced as a European seeking “haven,” (from what, it is unclear) in the United States. What better place to seek refuge than American suburbia! In an excerpt from a summary of the film, the neighborhood is described as follows: “We're really very fortunate here in West Ramsdale. Culturally, we're a very advanced group with lots of good Anglo-Dutch and Anglo-Scotch stock. And, uh, we're very progressive - intellectually” (Dirks, Lolita (1962)). Not only does this reference seek to point out the societal prejudices of the time, but it also slightly revels the dark undertones of the story, giving a sense of uneasiness as to what ‘progressive’ actually refers to in this case.

Lucky for Humbert, an Ohio housewife, widowed for seven years, is all too eager to rent a room to such a successful bachelor. The persona of the weak, sexually starved, and desperate 1950s housewife boldly emerges early in Nabokov’s novel. Synopses of both the novel and movie versions of Lolita are void of details regarding Charlotte Haze’s life outside her emotional longing to become Humbert’s partner. She is described a “wealthy widow” and her role in the novel is to model the deep seeded angst and sexual frustration felt by so many women in the 1950s. Humbert, put off by Charlotte’s pushy demeanor, hesitates to take up residence with her, until he lays eyes on her unusually seductive, “nymphet” daughter- Lolita. A juxtaposition of characters is immediately evident- Charlotte seems to represent the housewife of the past, content in her lot, happy to be subservient even to her late husband and eager to live in the shadow of her next love interest, seeking only to love him and accept his love in return. Such lines like, “Ohh, I'm lonesome...I think it's healthy for me to be jealous. It means that I love you. You know how happy I can make you” (Dirks), epitomize the housewife image of the time. In contrast, Nabokov’s Lolita is perhaps his symbol for the woman of the future- a product of a demanding etiquette which requires a woman to suppress her libido and deny lust and even instinct. Lolita commands her sexuality, it exudes from her every action, and Humbert is immediately enraptured by her intensity. A very sordid love affair ensues between the professor and his young lust interest; in fact Humbert marries the vapid Charlotte just so he can later be with Lolita. But the whole affair eventually turns into a disaster when Humbert’s hunger for Lolita consumes him and feeling dominated by him, Lolita rebels and ultimately gets taken advantage of by another older man and ends up in a lower-class slum, pregnant and without money. Humbert goes on to murder the man who stole Lolita away from him and dies in prison while awaiting his trial. The tragic ending to the story only reinforces the pertinence of Nabokov’s social commentary.

That Lolita’s modern promiscuity ends perilously for all those involved might serve as a warning to the people of the 1950s. Not a warning that says, ‘Don’t be like Lolita!’ But rather a warning about a dangerous trend in 1950s society- perhaps such staunch resistance to human nature and sexuality causes a very unsettling dynamic within a culture, a dynamic which could result in an unhealthy eruption of emotional detachment and rage even. While considered very risqué for the time, I believe Lolita brought about a much needed social awareness and piqued an interest in people’s subdued cravings for something edgy, off-beat, and disturbing even.

WORKS CITED

Dirks, Tim. Lolita (1962). Greatest Films: 1996-2006.,/a> Online. 18 October 2006.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home